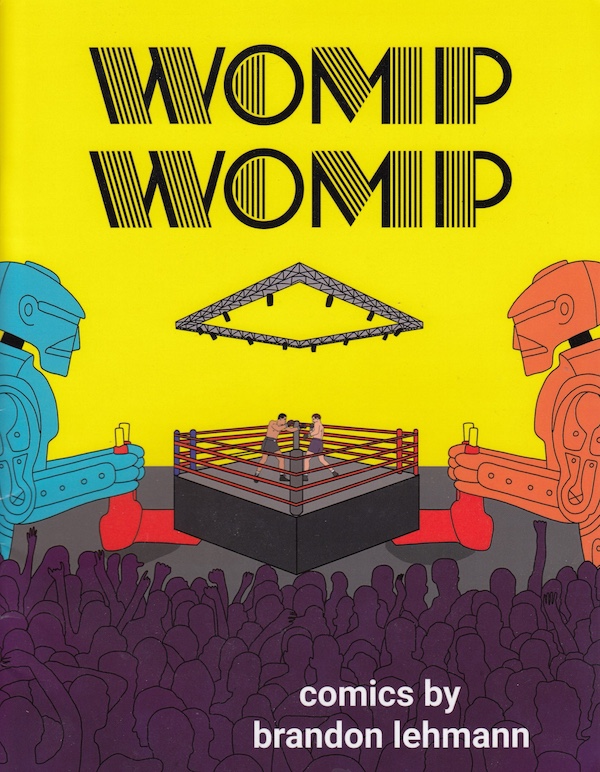

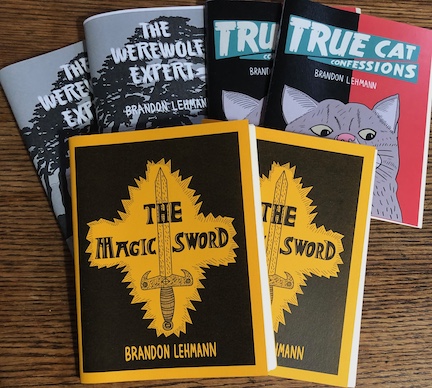

Brandon Lehmann may not see himself as a prolific mini-comics creator, but a look at his back catalog of titles tells a different tale. Brandon has created dozens of mini-comics, in series form (Womp, Womp, The Wizard, G-G-G Ghost Stories, etc.) as well as one-offs (The Magic Sword, The Werewolf Expert, et al.)

Brandon’s style consists of deadpan humor, sly satire, and nonplussed protagonists set against a static background that creates the feel of a surrealist cartoon.

A midwesterner by birth, Brandon now calls Seatle home where he is part of a thriving indie comics scene comprised of new-comers, old-timers, and in-betweeners.

And were you aware that he was once an electronic music producer known as Bobby Mono? Well, read on… — Chris Auman, 2024

REGLAR WIGLAR: You are a pretty prolific comic creator. How many titles have you published in your prolific comics-creating career?

BRANDON LEHMANN: If you’re looking at my back catalog, it would certainly seem like a lot. I’ve probably self-published somewhere around 50 mini-comics and three graphic novel-length books and a countless number of comic strips. But if you consider that I’m just doing this as a hobby for 15 years, that seems like a low output compared to someone who’s pursuing comics as a career. Supposedly at his peak Jack Kirby was killing between three and five pages per day.

One of the great things about indie/self-published comics though, is you have more freedom to focus on the content and message of your story in a thoughtful way instead of just churning out page after page of superheroes throwing punches.

My own relationship with creative output is kind of a minor mental health issue. When I’m not working on something I actually feel guilty, like a Catholic that has abandoned their faith. I find that a good way to stay productive is to be constantly working on multiple projects, just moving the goalposts till you finish something.

RW: What was the first title you published? How did others receive it at the time and what do you think about it now?

BL: I was an electronic music producer involved in the rave scene in Indiana at the end of the late 90s/early 2000s under the name Bobby Mono. I made sample-based dance music and had produced a couple albums worth of IDM and drum and bass that are still available on Bandcamp. Through that I got interested in making my own album covers and ended up creating a comic character also called Bobby Mono that was basically a stylized stickman.

By my late 20s, my music career had kind of fizzled out and I started posting comics on Deviant Art where I connected with people like Henry Eudy and Luke Pearson who now has several Hilda books and a Netflix series based on them.

My first book was a satire of EC horror comics featuring Bobby Mono strips called “Tales of Mild Discomfort and Anxiety.” The art was really crude and the jokes not so great, but the cover featured Cthulhu so people bought it strictly based on that, haha.

RW: You live in Seattle. Are you from the area or did you move there to be a part of the comics scene/community there?

BL: I’m originally from a suburb of St. Paul, Minnesota. I had been drawing and writing short fiction and poetry all throughout my childhood. Between 1994 and 1996, I made a high school zine along the lines of The Onion. I graduated from Indiana University in 2001 with a degree in art and English, and then just kind of arbitrarily decided to move to Seattle in 2002.

RW: What other Seattle-based comic artists do you like/know/or work with?

BL: Seattle is fortunate to have one of the most vibrant and connected comics scenes in the US. The people here love indie comics.

Shortly after I put out my first comic book, I met Kelly Froh and Max Clotfelter. Kelly later went on to put together “Short Run,” one of the best indie comic conventions in the country and Max started “Dune,” a monthly comic meetup where what seemed like all of the active artists in the city got together to make a joint comics zine. “Dune” was later taken over by Marc Palm and it ended up lasting almost 10 years until COVID.

Also because Fantagraphics Books is headquartered in Seattle, we kind of take for granted that we get to see comic legends like Pete Bagge, and Jim Woodring just walking around on a semi-regular basis.

Simon Hanselman used to live here for a long while and Alex Graham still does. What I’m saying to people that don’t live here is that the streets here are basically paved with comics gold haha.

I was a late-issue member of The Intruder, a comics newspaper edited by Marc Palm. In addition to the founders Marc and Max, James Stanton, Ben Horak and Tom Van Deusen, The Intruder had a revolving list of contributors like Josh Simmons, and David Lasky.

I’ve also done work for the comic newspapers that followed after — Thick as Thieves, and Scarfff which is still going on today.

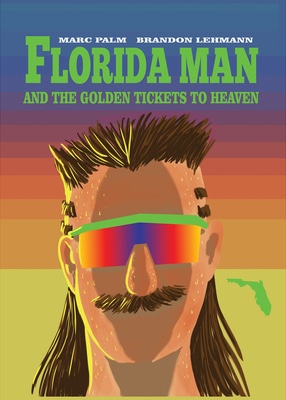

As a publisher, I’ve co-written Florida Man with Marc Palm, who was Eisner nominated for a comic in Mad Magazine. Sarah Romano Diehl and I also worked together on a parody of the film I Know What You Did Last Summer called I Like Totally Know What You Did Last Summer.

RW: Your comics, while not animated, of course, remind something you’d see on Adult Swim but in comic form. Have cartoons influenced your comics in any way?

BL: I do all of my comics 100 percent digitally nowadays, and several of my comics are kind of an analog type of animation with a lot of repetition of art with subtle changes as you advance between the panels. Part of this is just a method to create a comic quickly, but I’m always trying to design my work so that it can work in just about any format of book and it could be almost effortlessly animated.

In traditional hand-drawn animation, you would have this beautiful elaborate painted background that is reused over and over with a simple character moving superimposed on top of it. So I’m kind of using the same approach.

My comic The Werewolf Expert is set in a Barnes and Noble and is a very conversational piece. For the background, I went to a Barnes and Noble and took a good long shot photo of the store area, and I kid you not, spent about 120 hours of work meticulously digitally inking the photo 1

That way I could take snippets of the artwork and plop them in the background behind the figures, in relation to where they were standing so no resolution would be lost in copying and pasting. Some of that doesn’t show in the printed version, but in the master art, you can literally read the title of nearly every one of 1,000s of books, haha.

For the purposes of a gag comic spending 20 hours on a background or a character is really really stupid use of my time. But I’m always trying to future-proof the art so that if one day I might want to reuse the same characters or background I have these easily modifiable art assets to work with.

I was a big fan of Sealab 2021 back in the day. They were basically taking existing animation assets from the Sealab 2020 show and reusing them to make something new. This concept also kind of tied back to my method for writing music with samples.

RW: Other than other comics and animation, what else inspires or influences you or your work?

BL: Since I didn’t really get into comics until almost my 30s, and I honestly didn’t even read comics at all, there weren’t really any artists that influenced the development of my style.

In my poor comics education at the time, it wasn’t until I read Underworld by Kaz that I knew that the concept of indie comics even existed.

Michael Kupperman’s Tales to Thrizzle series was a big inspiration for me. He puts a lot of artistry into comedy comics that don’t really need to be so well drawn.

I’m a big fan of Nick Maandag. He’s making some of the funniest comics in the world right now and his dry-humor slow-burn writing style that just builds and builds to a hilarious payoff has had a big influence on my longer comics.

Some of my other favorites are Dan Clowes, Junji Ito, Yoshikazu Ebisu, Yoshiharu Tsuge, Dylan Dog by Tiziano Sclavi, Josh Pettinger, Max Clotfelter, and November Garcia. They are the short list of artists that don’t sit in an unread doom pile next to my bed for eight months, LOL.

When I was younger, I had always wanted to be a stand-up comedian, but I realized after a few attempts that I’m not a great performer. A lot of my auto-bio scripts are my attempt to translate what I would do as a stand-up in comic form.

Kids in the Hall is a big influence, I see a lot of my work as kind of an absurd sketch comedy sketch. I also find myself going a lot to old art books and vintage photographs for inspiration on composition.

RW: How do you feed yourself when you’re not making comics? Day job? Gig economy-participant? Freelancer?

BL: My day job is in electrical construction sales. I was an electrician for 12 years and this is kind of a desk job where I’m looking at blueprints, designing systems, and preparing cost estimates. It’s a very left-brained highly skilled job that makes it so I don’t have to worry about money. It also has a lot of overlapping skillsets with being a successful comic artist-deadlines, dealing with rejection, and constant existential despair.

I feel like if I did art for a job it would be very hard to want to work on it in my free time. Because I’m fortunate there, I’m not forced to constantly hustle for money and can take on projects that I actually want to do.

RW: Can you spend as much time as you’d like making stuff? Is that even possible?

BL: Of all the stages of making a comic (write/pencil/ink/letter/color), I think my greatest strength is writing. I’m sure it’s something a lot of people struggle with. I’m like a Stephen King or a Tom Clancy character where at any given moment I could give you 3,000 plot outlines for a story. Hell, I could probably do it for any general topic just off the top of my head.

Meanwhile, I’m a completely self-taught cartoonist and it will take me ages to bring a story from script to colored because I’m just frankly not very talented at it and it takes ten times as long. People who haven’t ever drawn a comic don’t realize the painstaking amount of work that goes into it. Executing a script can sometimes be complete misery for me, and it’s especially soul-crushing when you spend two years drawing something that nobody likes.

Two paragraphs in I’m now realizing that I didn’t really answer your question. I think the only way that any of us could probably spend as much time as we’d like is if we lived in some kind of pocket dimension where time doesn’t exist, haha.

RW: What’s your process for creating a comic? Are they tightly scripted or do you just riff on a general idea?

BL: For me it all begins with a loose script that I’ll modify on the fly as I’m drawing. I use Microsoft OneNote a lot and anytime I have a funny conversation or come up with a funny concept I’ll write it down to sprinkle it whenever it works. Writing for comics, and especially jokes is an art form of wording something so that it’s perfect, with perfect timing, and as succinctly as possible. Sometimes I’ll post a comic to the internet only to come up with a better joke or better wording after the point of no return. GAH!

For a while, I’ve stopped using a consistent character, like I’m talking about a Charlie Brown/Garfield, et cetera here. If you’re working with a character you can tend to build off of previous stories for jokes. The characters in my comics have basically become the joke and the people in the drawings are just kind of paper tigers that are saying the words.

Because a few years ago I started working all digitally, I became lazy and also stopped penciling. People who can draw, who can actually draw are great at that, and of course, any part of art is like exercising a muscle, where the more you work at it the better you get. But I’m complete shit at that.

When I start working on something I will spend a lot of time looking at stock photos on the internet for the inspiration of what my temporary character will look like. A lot of the time I’ll take field trips for reference photos, and then I’ll cobble it all into a digital collage that I directly ink on top of.

There’s maybe a philosophical battle between the artist that builds something from scratch using tools and the artist that is more concerned about the end product than how they got there. I’m a hack and the latter, but I guess I’m not concerned about it.

RW: I first saw your stuff on Instagram, I was wondering how you felt about using that platform to promote your work. A necessary evil? A valuable marketing tool? Total time suck?

BL: God only knows if all the conspiracy theories about algorithms trying to screw us over are true about social media. It took me a long while of self-reflection and mental health days but I think I can finally say I DGAF about likes or follows anymore. Wise people have always told me that you need to make art for yourself. Social media makes that very difficult, but you just have to meditate about it to get rid of all the mania, and delusion, and paranoia.

The main thing that I like about Instagram for comics is that they give you a max of ten panels, and in between each panel, your reader has an automatic pause. Not very many people use the platform this way but that automatic pause is great for both comedy and horror because every swipe is a big reveal, so you can write your story to lead up to an unexpected surprise.

Maybe I don’t have a million followers because I’m trying the patience of my audience, but it’s a lot funnier to do it that way. You’re forcing the audience to interact. It’s really affected the way I plan out the story even in a book, so when you turn a page you get a big laugh because you’re not expecting something.

RW: How else do you get the word out about your comics and where can people find them?

BL: I generally post everything I do on Instagram @brandon.lehmann.

I run a publisher of mostly myself and a few other artists called Bad Publisher Books that has a store on Storenvy. Always looking for funny artists to work with on small print-run comedy comics.

Recently, Microcosm Publishing republished a few of my most popular selling comics “True Cat Confessions,” “The Werewolf Expert,” and “The Magic Sword,” that can be ordered through their website to carry in your local comic shop or retail store. Almost all my work is available at the Fantagraphics Bookstore in Seattle, and Partners and Son in Philadelphia.

My basement is also a great place to find my comics if you ever want to stop by.

In 2024, I’ll be putting out a mini-comic called Dog Restaurant that will surely upset dog lovers everywhere. I’ve been working for a few years on a comedy/horror graphic novel called The Legend of Pum’kin Jack that is a parody of slasher horror movies. And my continuing series Womp Womp and G-G-G-Ghost Stories will surely get a new issue in the near future. I’ll just keep churning them out until eventually I die.

RW: Well, on that note …

Thank you for reading this reading this interview about Brandon Lehmann Mini-Comics. Read more interviews here.